How to Make Environment Concept Art and Level Design in One Sprint

Balancing Artistic Elements and Usability in Level Design

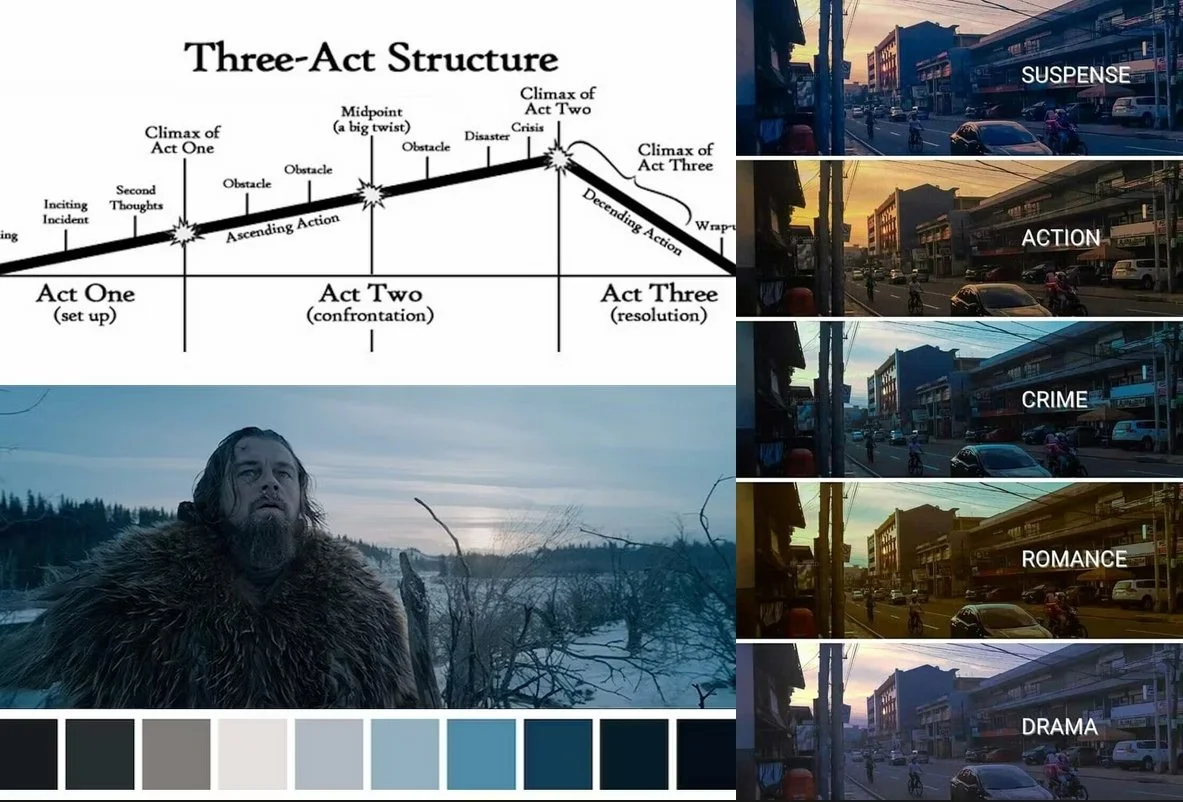

How do we balance artistic elements, narrative, and usability in design? We begin by ensuring the block-out of the level design respects the fundamental principles that make it work. In my free level design manual, I quickly go over some of these, such as how to build safe zones and how to create interest and control the narrative in your game.

Once you decide what to do and what your goal is with the level design, that process should shape the levels. After that's out of the way, we can make decisions that are best for the game’s aesthetics and narrative beats.

Architecture, of course, plays a big part in this. You want the set to feel believable. If you're designing a town in the Dark Ages, you want players to feel immersed in that story. This has less to do with level design and more with mood and story, but ideally, you want to sync the level design with the story.

For instance, if a chapter of the game is meant to make you feel fear because of a lurking monster, and you also want the player to advance the narrative, a good way to do both is to make your hallways feel claustrophobic, narrow, and in all ways possible, only allow forward exploration of the map.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to this. Because I'm only covering the monster chase (mood and story) and level design (narrow hallway), it's not just that one supports the other; they are in a relationship with one another, part of a cohesive whole.

This is what games as a medium do well and better than movies or other media. It's an interactive story. You can take part in it and experience it.

The Level Design Thinking Process

Most of the environment concept art I design for games isn’t flashy or trendy, but my focus is on level design, usability, and player experience. The goal is to make sure games are fun and have replay value, like the old Fallout games where you restart to try a different path out of curiosity about all the choices you can make.

The process goes like this:

Think about how people will use the spaces. Make it realistic, not just a pretty picture. After reading Atomic Habits by James Clear, I started paying more attention to how people move around and how the environment shapes behavior, thinking like an architect. For example, if I'm making a town, I ask, "Should the water well be in the middle of the town square so people can trade, socialize, and take care of other things at the same time?"

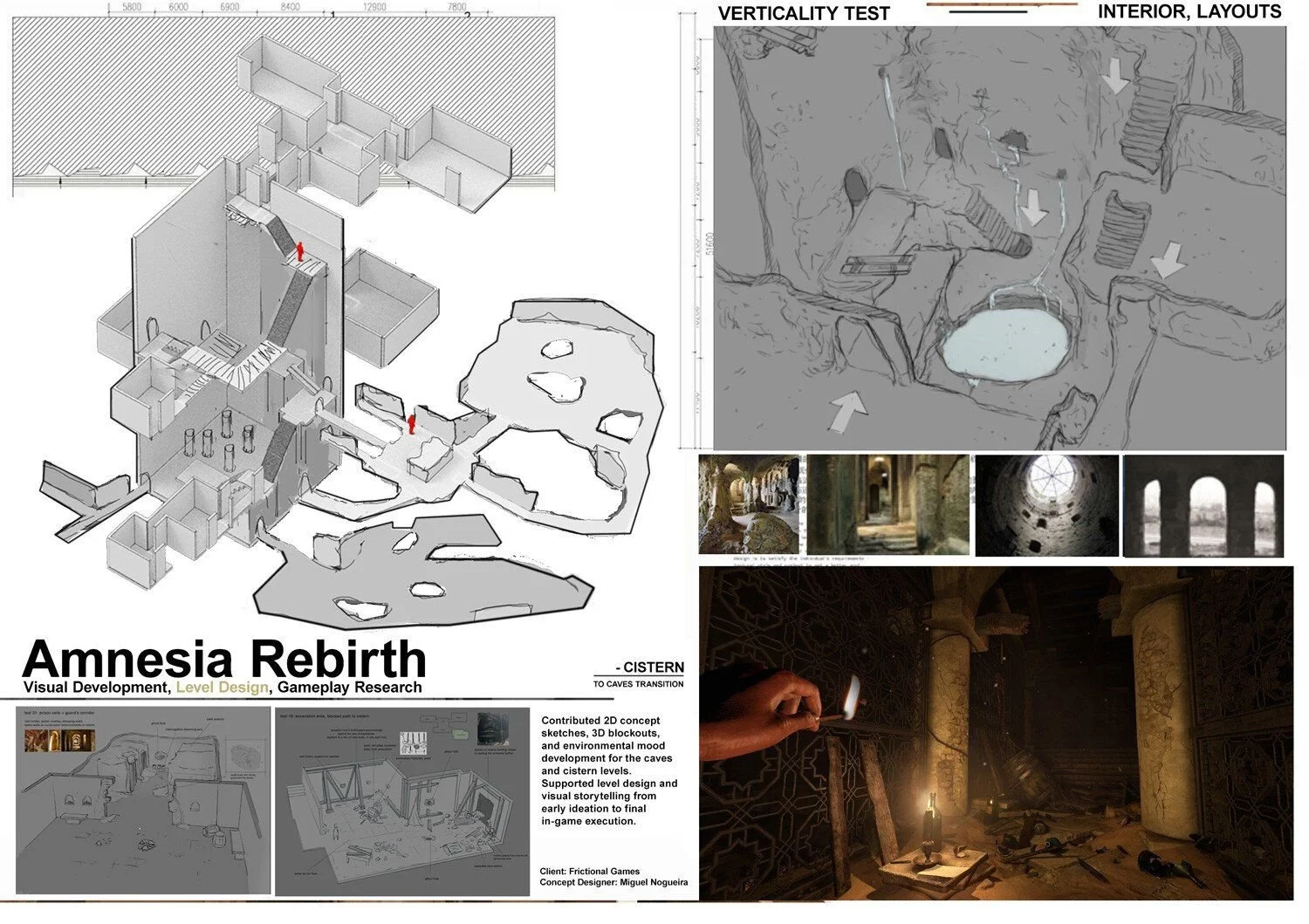

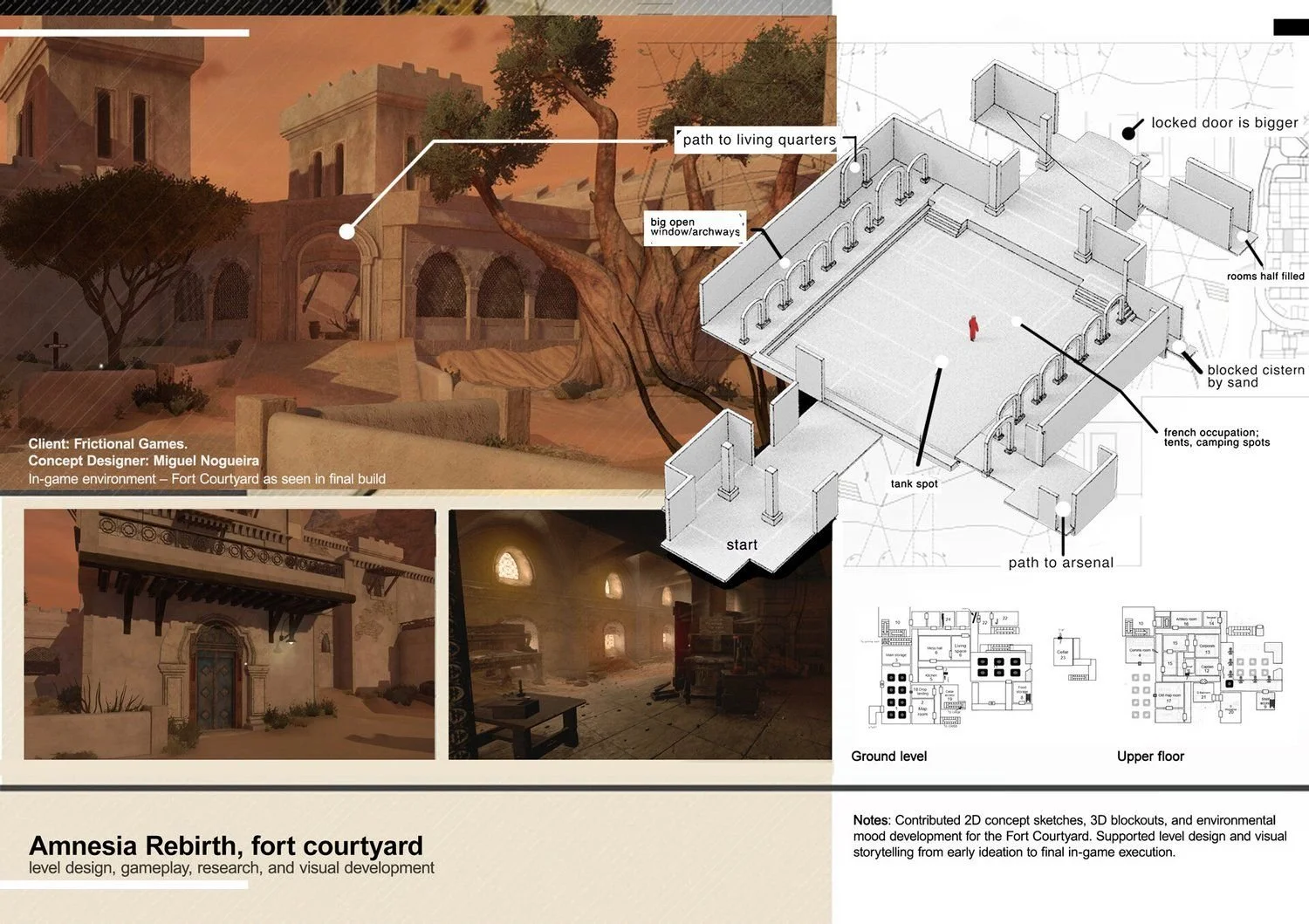

The most important part is the level design. To make a place fun to play, I first build the levels as 3D cubes. I overlap empty spaces, doorways, windows, and fences and show parts of the level from far away without revealing everything. This makes players curious and they'll want to keep exploring. I helped design about 3 out of every 10 parts of the levels in Amnesia: Rebirth and also made 80% of the art, including props, lighting tests, and interactive objects, as well as some characters.

You can find that case study, tips, and other resources in the next sections of this blog.

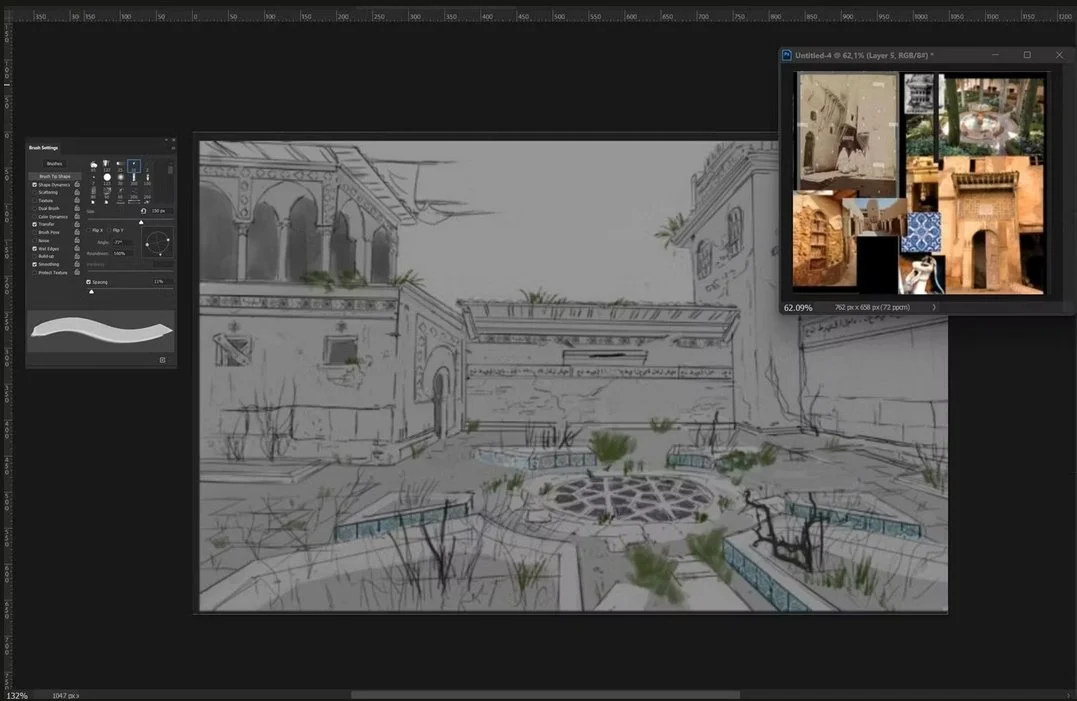

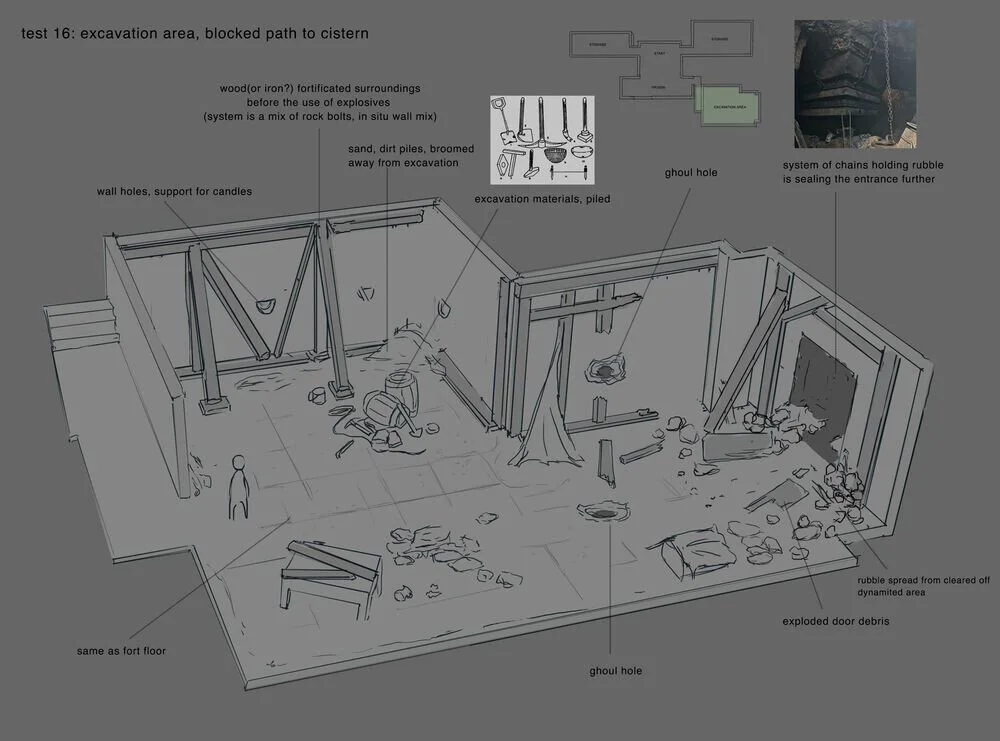

The Art of Environment Line Drawings and References

Line drawings like these take me about 30 minutes to an hour. They bring just enough detail to draw over the level block-out, and I use photo references to fill the gaps in any ambiguous linework. People respond to different levels of detail. Some studio decision-makers respond well to a polished image, while others, like Art Directors, find it easier to read a less polished sketch. Bringing in these photo references helps bridge that gap as quickly and efficiently as possible.

If you're not sure how to design these, that's normal; it's a lot to take in.

Here's one way I like to start: draw something rough, like this, and then evaluate if it fits the project's needs. It'll be easier to change it midway before you commit to a polished illustration that is of no use to the project.

In this old screenshot from Amnesia: Rebirth, a game I worked on as Principal Concept Artist, we see the Fort in the distance. We haven't had much chance to glimpse something like it so far in our travels through the desert, and we still don't fully see it. But we know, as players, that's where we want and need to go. This is the sweet spot: designing an experience the player wants to have and one they need to have to advance in the game. By showing just enough of the Fort's silhouette, you invite the player to keep moving forward, reaching the Fort and starting a new chapter.

Did you ever get stuck in production while trying to balance Level Design, Function, Narrative Design, and Concept Art all in one?

Download my free cheat code manual on Level Design and apply these theories to your project! If you need something not covered by the manual, reach out to me by email, and let’s discuss something custom for your project.

About the Author

Miguel Nogueira is a Concept Artist and Art Director with over 15 years of creative industry experience. He has contributed to projects and studios such as Sony PlayStation, Wizards of The Coast, Embark Studios, and DICE, and is currently leading projects for both board games and animated series. While this work will be released soon in his portfolio, you can find more on his front page portfolio for now.