How I Deliver Concept Art 300% Faster, without AI

So, looking back at my time as a Concept Artist at Frictional Games, I managed to get things done way faster than what's usually expected – around 300% faster, to be precise (and no, wasn't using AI back then). Plus, the quality of the final art jumped from standard 2D painting to proper photo-realism. This shift had a real impact on how we worked, and I even ended up delivering 3D models that helped the pipeline move along about 80% quicker.

So, how did I pull that off?

It came down to setting up a material library that was focused but had everything we needed, along with a solid style guide. Now that I'm freelancing as a concept artist and director, working with indie studios and some AA teams, this is the kind of thing I see them struggling with the most. Getting a strong base for your world's look and feel is super important.

The setup to deliver faster concept art without losing creativity:

Step 1: Really Looking at Your Materials

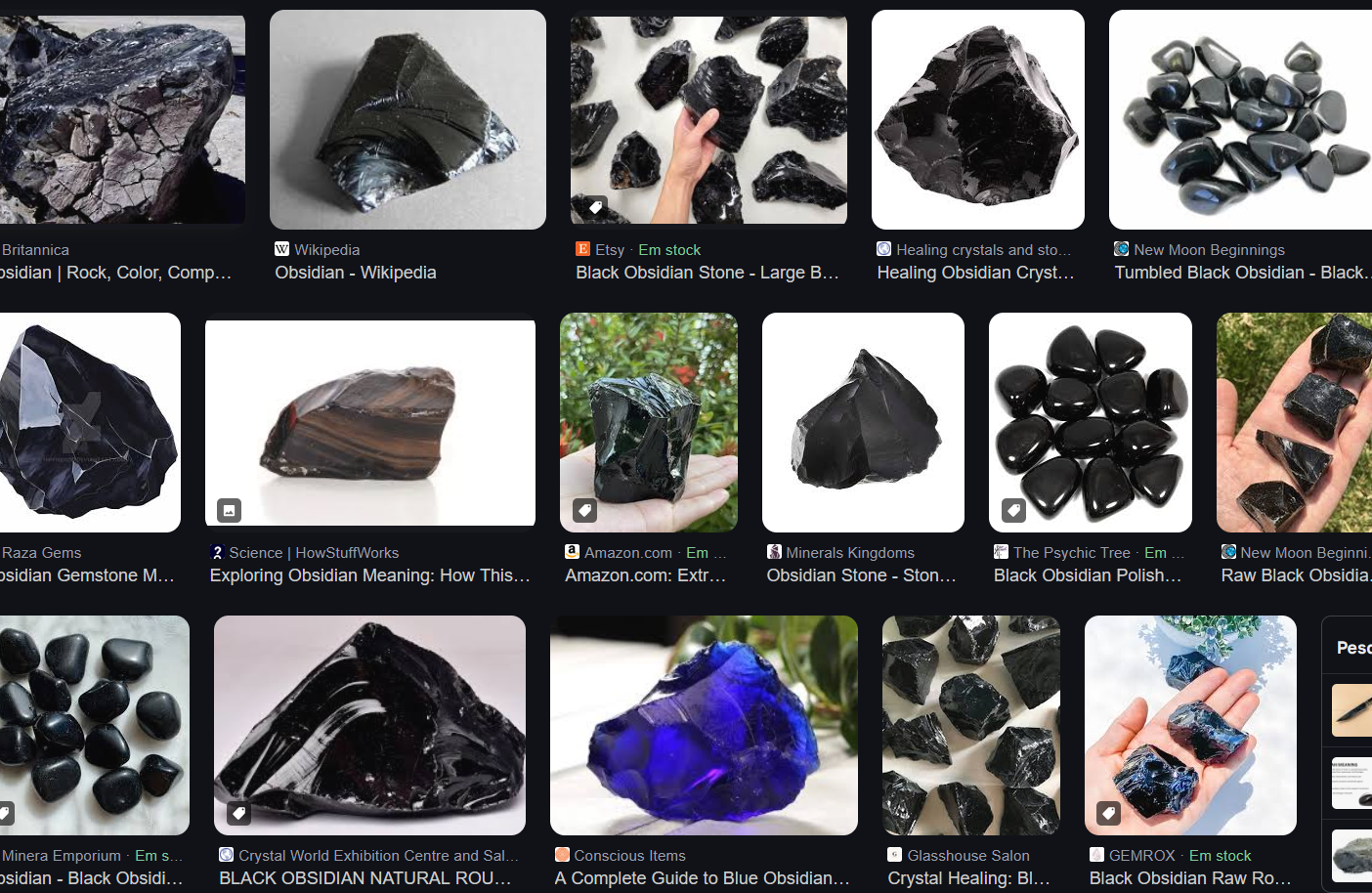

What I did first was properly study the materials that would be common in the game. Let's take these as an example:

It's about taking a step back and actually checking out things like the Fresnel effect, how light bends (refraction), and how reflective different parts are. How does light act in the real world when it hits these materials?

You don't need a fancy degree or anything for this. Just knowing the basics of what these terms mean – you can honestly pick that up in a morning while scrolling through Wikipedia or even watching a cool documentary on YouTube, like something from National Geographic. You can start to just eyeball the look and feel of a material until, say, the metal you're making actually looks like metal on your screen.

Trust me, it's not as hard as it sounds. If all the technical stuff puts you off, you can totally just go by what looks right.

Like Dali said, don't be scared of trying to be perfect, 'cause you'll never get there anyway. So, don't worry about making a mistake or two. As long as it tricks people into seeing metal or whatever material you're going for, it's good enough. Because what you see on the screen is always just a perception; it's never going to be exactly like the real thing – it can't be, because it isn't.

Keeping Things Limited (But Useful)

Having a limited set of materials actually helps you figure out what you can work with. Usually, a game or film project will only have so many different materials anyway. For example, if you're working on a fantasy game set in the Iron Age, you're obviously going to be sticking to a certain range of materials. And that's what we do – we build those materials as we need them.

Each of these materials took me about 10 to 30 minutes to put together in Keyshot's material graph. Up here, you can see an obsidian stone (man, I love geeking out on these! There's something really magical about them). The more you craft these, the faster you get.

This is a good start, but here's the thing about software – it's just a tool. Tools help you get to an end result. I'm a big fan of mixing all the software you can get your hands on. I don't buy into that idea of one perfect tool that's going to change everything and be the only thing you ever use. They all have their good and bad points. That said, I noticed that while Keyshot got me a texture and feel I liked for obsidian, some things were missing.

Remember how I said you don't need a PhD in this stuff? You can just eyeball it. And this part of the process kind of becomes like playing around. You can try to spot the differences between your render and photos of real obsidian! One thing that really stands out is how reflective they are, so I'd simulate a gloss layer in Photoshop, using screen mode, to bring that shine into the picture.

We're not doing hardcore 3D art here, technically speaking; we're concept designing. So, it's totally okay to use 3D and Photoshop. The final thing is going to be a JPG anyway.

I really want to point out that this is an art, not a science. It doesn't really matter that I specifically set things to screen mode in Photoshop. This isn't a step-by-step recipe. Screen mode just gets rid of most of the dark areas in an image and keeps the lighter transitions, which is what I wanted for the obsidian. But it could have just as easily been a 'lighten' mode. It really depends on what you're working on. I just don't want you to think this is some kind of rulebook. Don't work by strict rules; rules are good for copying what you've already done, not for making something new.

Last but not least, using 3D lets you break down your props, try out different versions, and really quickly, you can end up with a whole family of furniture, weapon designs, or whatever else you need to fill out the scene. This saves a 3D modeler a ton of time because they don't have to start from scratch, and they can just focus on making sure the models are clean and run well in a 3D game engine.

With 3D concept art in your process, you get the benefit of looking super realistic, but you can also turn the model around, render it from different angles in real-time, without any extra render time or cost – boom, done! Everyone wins. While I first started doing this to make it easier for the 3D artists to understand the concept, a lot of other good things came out of it too, as you can see.

About a Style Guide / Material Library:

By the end of that project at Frictional, I must have had around 30 different materials, give or take, for each environment in the game. Whenever we needed to use obsidian, metal, or any other material again (which was pretty much all the time), I didn't have to make it from scratch. I'd just drag it from Keyshot's material library, drop it in, and render! This saved me the initial research time – about 30 minutes max per prop – and I was able to churn out an average of 4-5 concept designs a day, fully rendered in different 3D views, with easy-to-follow notes and a basic 3D model, all while further developing the style guide.

It even works with plants!

And functional props!

One of the big pluses of working in 3D as a concept artist is that you really get how things work. You can't really make stuff that wouldn't function in reality. By working with 3D forms in real-time, everything just naturally fits within the right scale, and it makes things way easier for the animation guys later on.

But 2D design is still super important for planning things out. Just jumping into 3D without a clear idea can actually waste more time than it saves. I always sketch something out first to make sure it at least looks like it could work. The problem with 2D is that sometimes you can get away with designs that look cool but wouldn't actually work in 3D... unless:

And hey, would you look at that, it works for character design too.

Here's a personal piece for a sci-fi thing I was playing around with, using this exact process:

Closing note about AI in Concept Art

By the end of this process, we had:

A library of materials, ready to be dropped into any 3D model, whether for concept or the game engine.

Ensured cohesion of aesthetics throughout the project.

Conceputalized and 3D modeled simultaneously.

Unused 3D models were repurposed for other 3D models or different problems.

A library of kitbash materials.

A style guide built concurrently, defining the art direction as we progressed.

One might argue that some of these steps could have been done using AI, such as the pre-visualization, and image iteration, and it is true they could, but they shouldn't. There's a lot of design in concept art; this process isn't just about making pretty images. An artist is best hired for a vision, with or without AI, not merely for their manual execution.

AI often makes ergonomic and design mistakes. Something that looks good enough on the surface may reveal itself to be functionally inadequate. Otherwise, all our real-world vehicles would look like Lamborghinis and be considered the best due to their aesthetics. We know that's not true, as things like bulldozers, forklifts, and others are needed not for their aesthetics, but for what they can do.

You could hypothetically introduce AI in image iteration, but design, especially functional design, doesn’t require image iteration as it doesn’t focus on aesthetics. It could make up for speeding up the visual storytelling part, but would come with the artist's vision as a trade-off; for something a competitor using the same tool would be getting. If you’d be fine with that, you’d maybe get 20-30% faster in the process, but have a bigger trade-off on creativity. For things such as chair props and uninventive designs for set dressing, AI could definitely be used, but again, so can a photo from Google Images. It’s sort of like re-inventing the wheel here, by using AI in this process.

I hope that was of use to you, or at least a mildly interesting TED Talk that was worth your scroll, if you happen to have any questions or comments, feel free to say hello.

About the Author: Miguel Nogueira

Miguel Nogueira is a freelance concept artist, designer, and director with over 20 years of kicking around in creative industries, and the last decade specifically in video games. I've had the chance to work with some cool studios like NetEase Games, Embark Studios, Archetype Entertainment, and DICE, to name a few. My work's even been featured on places like CGSociety Hall of Fame, Behance, Kotaku, and 3DTotal.

Want to Level Up Your Project's Visuals? If you're looking for a concept artist who can bring speed, quality, and a smart workflow to your project, or if you're interested in having me speak at your event or sponsor my content, shoot me an email at: contact@menogcreative.com